What Aging Really Means — And How Science Says You Can Stay Stronger, Longer

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve noticed small but real shifts — less energy, slower recovery, skin that doesn’t bounce back like it used to. I started digging into what aging truly is, beyond wrinkles and gray hair. What I found wasn’t about reversing time, but working *with* biology. Aging is not a disease, but a natural biological process influenced by genetics, lifestyle, and environment. The exciting part? Science now shows that many aspects of aging are modifiable. This means that while we can’t stop the clock, we can influence how we age — preserving strength, clarity, and vitality far longer than previously believed. The key lies not in miracle cures, but in consistent, science-backed choices that support the body’s innate ability to renew and repair.

Understanding Aging: It’s Not Just Wrinkles

Aging is often viewed through the lens of appearance — gray hairs, fine lines, a slower pace. But beneath the surface, a far more complex process is unfolding. Chronological age, the number of years since birth, is fixed. Biological age, however, reflects the functional state of your cells, organs, and systems, and it can differ significantly from your calendar age. Two people of the same chronological age may have vastly different biological ages based on lifestyle, genetics, and environmental exposure. This distinction is crucial because it means aging is not a one-way decline but a dynamic process that can be influenced.

At the cellular level, aging involves several interconnected mechanisms. One of the most studied is telomere shortening. Telomeres are protective caps at the ends of chromosomes, similar to the plastic tips on shoelaces. Each time a cell divides, these telomeres shorten slightly. When they become too short, the cell can no longer divide and enters a state of senescence or dies. This process is linked to tissue aging and reduced regenerative capacity. However, research shows that lifestyle factors such as chronic stress, poor diet, and lack of exercise can accelerate telomere shortening, while healthy habits may help preserve their length.

Another key player is oxidative stress, an imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants in the body. Free radicals are natural byproducts of metabolism, but when they accumulate, they can damage DNA, proteins, and lipids. Over time, this damage contributes to cellular dysfunction and aging. Mitochondria, the energy-producing structures within cells, are both sources and targets of oxidative stress. As mitochondrial function declines with age, energy production drops, leading to fatigue and slower recovery. Yet, studies indicate that regular physical activity and nutrient-rich diets can support mitochondrial health and reduce oxidative damage.

A common misconception is that aging inevitably means decline. While certain changes are natural, such as a gradual decrease in muscle mass or metabolic rate, severe deterioration is not a given. The emerging scientific consensus emphasizes that up to 75% of how we age is influenced by lifestyle, not genetics. This means that choices around movement, nutrition, sleep, and stress management play a dominant role in determining long-term health. Rather than accepting aging as passive decline, modern science encourages a proactive approach — one that supports cellular resilience and functional independence well into later life.

The Role of Inflammation: The Silent Accelerator

Chronic low-grade inflammation, often referred to as “inflammaging,” is now recognized as a central driver of biological aging. Unlike acute inflammation, which is a necessary and protective response to injury or infection, chronic inflammation operates silently in the background, slowly damaging tissues and impairing organ function. It is linked to a wide range of age-related conditions, including heart disease, cognitive decline, arthritis, and metabolic dysfunction. What makes inflammaging particularly concerning is that it often goes unnoticed until symptoms emerge, making it a stealthy contributor to accelerated aging.

The roots of chronic inflammation are deeply tied to lifestyle. Diets high in refined sugars, processed foods, and unhealthy fats can trigger inflammatory pathways. Excess body fat, especially visceral fat around the abdomen, acts as an active endocrine organ, releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines. Chronic stress also plays a significant role by increasing cortisol levels, which, over time, can dysregulate the immune system and promote inflammation. Sedentary behavior further compounds the issue by reducing circulation and impairing the body’s ability to clear inflammatory markers.

The good news is that inflammation is modifiable. Scientific studies consistently show that lifestyle interventions can significantly reduce inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). One of the most effective strategies is adopting an anti-inflammatory diet rich in whole foods — vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds, fatty fish, and olive oil. These foods contain antioxidants and polyphenols that neutralize free radicals and calm inflammatory responses. Regular physical activity, even moderate walking, has been shown to lower systemic inflammation by improving circulation and enhancing immune regulation.

Stress management is equally important. Mindfulness practices, deep breathing, and sufficient sleep all contribute to a balanced immune response. Additionally, maintaining a healthy gut microbiome through fiber-rich foods and fermented products supports immune tolerance and reduces inflammation. The cumulative effect of these choices is not just symptom relief but a fundamental shift in the body’s internal environment — one that supports tissue repair, metabolic efficiency, and long-term resilience. By addressing inflammation at its source, individuals can slow biological aging and maintain better health over time.

Movement as Medicine: Why Your Cells Love Activity

Physical activity is one of the most powerful tools for healthy aging, with benefits that extend far beyond weight management. At the cellular level, movement influences gene expression, mitochondrial function, and tissue repair. Exercise activates pathways that enhance cellular cleanup (autophagy), reduce oxidative stress, and support telomere maintenance. It also stimulates the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that supports cognitive function and neuroplasticity. In essence, every time you move, you are sending beneficial signals to your cells that promote longevity and resilience.

Different types of movement offer unique advantages. Strength training, for example, is essential for preserving muscle mass and bone density. After age 30, adults lose about 3–5% of muscle mass per decade, a condition known as sarcopenia. This loss contributes to weakness, reduced mobility, and increased fall risk. Resistance exercises — whether using body weight, resistance bands, or weights — stimulate muscle protein synthesis and help counteract this decline. Even two sessions per week can make a measurable difference in strength and functional independence.

Endurance activities like brisk walking, cycling, or swimming improve cardiovascular health and mitochondrial efficiency. These exercises increase oxygen delivery to tissues, enhance insulin sensitivity, and support heart function. Flexibility and balance practices — such as yoga, tai chi, or stretching routines — are equally important. They maintain joint range of motion, reduce stiffness, and improve coordination, which becomes increasingly valuable with age. A well-rounded routine that includes all three types of movement supports full-body function and reduces injury risk.

The key to long-term success is consistency and adaptability. Science supports the idea that even small amounts of daily activity are beneficial. A 10-minute walk after meals, a few minutes of bodyweight squats, or gentle stretching can accumulate into meaningful health gains. For those with limited mobility or health concerns, low-impact options like water aerobics or seated exercises provide accessible alternatives. The goal is not intensity but regular engagement. When movement becomes a natural part of daily life, it ceases to feel like a chore and transforms into a sustainable habit that nourishes the body at every level.

Nutrition That Supports Longevity — Not Just Weight Loss

Nutrition plays a foundational role in how we age, yet many people focus solely on weight loss rather than long-term metabolic health. The shift from dieting to nourishment is critical. Rather than restrictive eating, the goal should be nutrient density — consuming foods that provide high levels of vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and phytonutrients with relatively few calories. This approach supports cellular function, reduces inflammation, and maintains energy levels without triggering hunger or metabolic slowdown.

Among dietary patterns studied for longevity, the Mediterranean-style diet stands out. Rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, olive oil, and fish, with moderate poultry and limited red meat and processed foods, it has been consistently linked to lower rates of heart disease, cognitive decline, and overall mortality. The benefits are attributed not to any single “superfood” but to the synergistic effect of whole, minimally processed foods. For example, olive oil contains oleocanthal, a compound with anti-inflammatory properties similar to ibuprofen, while fatty fish provide omega-3 fatty acids that support brain and heart health.

Protein intake becomes increasingly important with age. Adequate protein helps preserve muscle mass, supports immune function, and promotes satiety. However, many older adults consume less protein than needed, especially at breakfast. Distributing protein intake evenly across meals — about 25–30 grams per meal — has been shown to optimize muscle protein synthesis. High-quality sources include eggs, Greek yogurt, lentils, tofu, poultry, and fish. Healthy fats, particularly monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, support hormone production, brain function, and nutrient absorption. Fiber, found in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and legumes, feeds beneficial gut bacteria and helps regulate blood sugar and cholesterol.

Hydration is another often-overlooked aspect of cellular health. As we age, the body’s thirst mechanism becomes less sensitive, increasing the risk of chronic dehydration. Even mild dehydration can impair concentration, digestion, and circulation. Drinking water throughout the day, consuming water-rich foods like cucumbers and soups, and limiting sugary beverages support optimal function. It’s also important to approach supplements with caution. While some, like vitamin D or B12, may be necessary for certain individuals, most people do not benefit from high-dose antioxidant or anti-aging supplements. In some cases, excessive supplementation can even be harmful. The best strategy remains a balanced, varied diet that provides nutrients in their natural, bioavailable forms.

Sleep and Recovery: The Underrated Pillar of Youthful Function

Sleep is a cornerstone of health, yet it is frequently undervalued in discussions about aging. During sleep, the body performs essential maintenance: repairing tissues, clearing metabolic waste from the brain, regulating hormones, and consolidating memories. Poor sleep quality or insufficient duration disrupts these processes, accelerating biological aging. Studies show that chronic sleep deprivation is associated with shorter telomeres, increased inflammation, and higher risks of chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension.

The relationship between sleep and aging is bidirectional. While aging can affect sleep patterns — leading to lighter sleep, more nighttime awakenings, or earlier waking — poor sleep habits can also make a person feel and function older than they are. Disruptions in circadian rhythm, the body’s internal clock, impair insulin sensitivity and increase cortisol levels, contributing to weight gain and fatigue. Therefore, maintaining healthy sleep hygiene is not just about feeling rested — it’s about preserving metabolic, cognitive, and immune health.

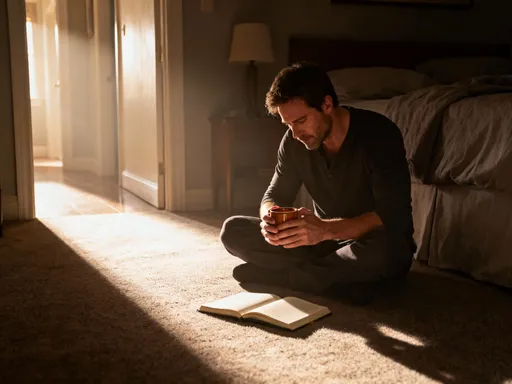

Improving sleep starts with consistency. Going to bed and waking up at the same time every day, even on weekends, helps regulate the circadian rhythm. Creating a calming pre-sleep routine — such as reading, gentle stretching, or listening to soft music — signals the body that it’s time to wind down. The sleep environment should be cool, dark, and quiet, with minimal exposure to blue light from screens at least one hour before bedtime. Avoiding large meals, caffeine, and alcohol in the evening can also enhance sleep quality.

While perfection is not necessary, consistency is. Even modest improvements — gaining 30–60 minutes of quality sleep per night — can have significant benefits. Napping can be helpful if kept short (20–30 minutes) and early in the day to avoid interfering with nighttime sleep. For those struggling with persistent sleep issues, consulting a healthcare provider is important to rule out conditions like sleep apnea or restless legs syndrome. Prioritizing sleep is not a luxury; it is a non-negotiable component of healthy aging that supports every other aspect of well-being.

Mindset and Stress: How Your Thoughts Shape Your Biology

The mind-body connection is not just philosophical — it is grounded in biology. Chronic stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to sustained release of cortisol, the primary stress hormone. While cortisol is essential in short bursts for energy and alertness, prolonged elevation can impair immune function, increase blood pressure, promote fat storage, and accelerate cellular aging. Research has shown that individuals with high perceived stress have significantly shorter telomeres, indicating that psychological stress can literally age the cells.

However, stress is not inherently harmful; it is the body’s response to it that matters. The ability to recover from stress — known as resilience — is a trainable skill. Mindfulness-based practices, such as meditation, deep breathing, and body scans, have been shown to reduce cortisol levels, lower inflammation, and improve emotional regulation. Even a few minutes of slow, diaphragmatic breathing several times a day can shift the nervous system from “fight-or-flight” to “rest-and-digest” mode, promoting healing and balance.

Daily routines that foster presence and gratitude also contribute to mental well-being. Keeping a journal, spending time in nature, or engaging in meaningful conversations can buffer the effects of stress. Physical activity, social connection, and creative expression all serve as natural stress relievers. The goal is not to eliminate stress — which is impossible — but to build a toolkit for managing it effectively. Over time, these practices rewire the brain to respond more calmly to challenges, reducing the biological burden of stress.

Importantly, cultivating a positive mindset does not mean ignoring difficulties. Rather, it involves approaching life with curiosity, acceptance, and a sense of agency. Studies suggest that individuals with a strong sense of purpose and optimism tend to live longer, healthier lives. This is not due to wishful thinking, but because a resilient mindset supports healthier behaviors — better sleep, more movement, stronger relationships — all of which reinforce physical health. By caring for the mind, we directly support the body’s ability to age well.

Putting It All Together: A Sustainable Approach to Healthy Aging

Healthy aging is not about chasing youth or achieving perfection. It is about creating a life that supports vitality, function, and well-being over time. The six pillars discussed — understanding biological aging, managing inflammation, staying active, eating for nourishment, prioritizing sleep, and cultivating resilience — are not isolated strategies but interconnected elements of a holistic approach. When practiced together, they create a synergistic effect that enhances overall health far more than any single intervention could achieve alone.

The most effective path to long-term success is not drastic change, but small, consistent actions. Instead of overhauling an entire lifestyle overnight, focus on one or two manageable shifts at a time. Perhaps it’s adding a serving of vegetables to lunch, taking a 10-minute walk after dinner, or turning off screens an hour before bed. These choices may seem minor, but their cumulative impact over months and years is profound. Progress, not perfection, is the goal. Sustainable change is built on repetition, not intensity.

Aging well is not defined by appearance, but by how you feel — your energy, strength, clarity, and ability to engage fully in life. It means being able to play with grandchildren, travel with confidence, cook meals with ease, and wake up each day with a sense of purpose. Science now confirms that these experiences are not reserved for the lucky few, but are within reach for most people who make informed, consistent choices. The habits that support healthy aging are accessible, affordable, and do not require special equipment or extreme measures.

Finally, it is important to remember that individual needs vary. What works for one person may not work for another. Always consult with a healthcare professional before making significant changes to diet, exercise, or supplementation, especially if managing chronic conditions or taking medications. Personalized guidance ensures safety and effectiveness. Aging is not a decline to be feared, but a phase of life to be lived with intention, wisdom, and care. With the right support and knowledge, it can be a time of continued growth, connection, and vitality.