Sleep Smarter, Not Harder: My Science-Backed Routine That Changed Everything

We’ve all been there—tossing and turning, hitting snooze five times, or surviving on coffee by 2 p.m. I used to think burnout was just part of adulting—until I discovered how deeply *sleep timing* impacts energy, focus, and mood. It’s not just about hours logged; it’s about rhythm. What if fixing your schedule could be the simplest, most powerful health upgrade? This is how science helped me reset—naturally. Over time, I learned that true rest isn’t found in sleeping longer, but in aligning with the body’s internal clock. And once I made that shift, everything from my concentration to my emotional balance improved in ways I hadn’t expected.

The Hidden Cost of Ignoring Your Biological Clock

Every cell in the human body operates on a 24-hour rhythm governed by the circadian clock, a biological system fine-tuned through evolution to respond to environmental cues like light and temperature. When this rhythm falls out of sync—due to erratic sleep, late-night screen use, or irregular work hours—the consequences extend far beyond tiredness. Disruption of the circadian system has been linked to impaired glucose metabolism, reduced immune function, and diminished cognitive performance. These effects may develop gradually, making them easy to overlook until symptoms become hard to ignore.

Consider the common experience of the mid-afternoon energy crash. Many reach for sugary snacks or caffeine, assuming the dip is simply due to lunch or a busy schedule. In reality, it may signal circadian misalignment—a mismatch between internal timing and external behavior. Similarly, difficulty falling asleep despite feeling exhausted often reflects a delayed melatonin onset, which can result from exposure to artificial light in the evening. These are not signs of personal failure but physiological responses to modern lifestyles that conflict with our biology.

Research from institutions like Harvard Medical School and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences confirms that chronic circadian disruption increases the risk of long-term health issues, including metabolic syndrome and mood disorders. Yet, most people remain unaware of how daily routines influence this delicate system. The body doesn’t just need sleep—it needs sleep at the right time. Recognizing the subtle signals of misalignment—such as inconsistent wake times, nighttime alertness, or morning grogginess—is the first step toward restoring balance.

Why “Just Sleep More” Isn’t Enough

For years, the dominant message has been simple: get eight hours of sleep. While adequate duration is important, recent studies in chronobiology show that timing and consistency are equally critical. A person who sleeps eight hours but shifts their bedtime by several hours each night may still experience what researchers call “social jet lag”—a state where the body’s internal clock is constantly playing catch-up. This misalignment can impair insulin sensitivity, disrupt appetite regulation, and reduce mental clarity, even in individuals who appear to sleep enough.

One landmark study published in the journal Sleep found that participants with irregular sleep schedules had higher body mass index (BMI) and poorer metabolic health compared to those with consistent bedtimes—even when total sleep time was similar. This suggests that the body thrives on predictability. When sleep times fluctuate, the brain struggles to anticipate when rest will come, weakening the natural buildup of sleep pressure and reducing the quality of deep, restorative sleep.

Moreover, irregular sleep patterns can interfere with the release of key hormones such as cortisol and growth hormone, both of which follow circadian patterns. Cortisol, often associated with stress, also plays a vital role in promoting alertness in the morning. When sleep timing is erratic, cortisol release may become mistimed, leading to fatigue upon waking or difficulty winding down at night. The takeaway is clear: sleeping longer does not compensate for inconsistency. True restorative sleep depends on regularity as much as duration.

How Light Shapes Your Wake-Sleep Cycle

Light is the most powerful external signal that influences the circadian clock. Specialized cells in the retina, known as intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs), detect light intensity and send signals directly to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the brain—the body’s master clock. When the SCN receives bright light, especially in the morning, it suppresses melatonin production and signals the body to become alert. This process helps anchor the sleep-wake cycle to the natural day-night rhythm.

Modern life, however, often disrupts this system. Many people spend mornings indoors under dim lighting, then expose themselves to bright blue light from screens late into the evening. This pattern confuses the brain, delaying the onset of melatonin and pushing the entire sleep cycle later. Over time, this can lead to a condition known as delayed sleep phase, where falling asleep before midnight becomes nearly impossible—even when tired.

To realign with natural rhythms, experts recommend getting exposure to bright natural light within 30 to 60 minutes of waking. A simple 20- to 30-minute walk outside in the morning can significantly strengthen circadian signaling. Conversely, reducing exposure to artificial light in the evening—especially from phones, tablets, and televisions—helps the body prepare for sleep. Using warm-toned lighting and enabling night mode on devices can further support this transition. By managing light intentionally, individuals can reset their internal clocks without medication or drastic lifestyle changes.

The Power of Consistent Wake-Up Times

Among all sleep hygiene practices, maintaining a consistent wake-up time is one of the most effective yet underused tools. Unlike bedtime, which can vary based on evening activities, wake time serves as an anchor for the entire circadian system. When a person rises at the same time every day—even on weekends—the body begins to anticipate this signal, reinforcing the natural rhythm of hormone release and sleep pressure buildup.

Sleep pressure, driven by the accumulation of a chemical called adenosine in the brain, increases the longer a person is awake. A stable wake-up time ensures that this process starts at the same point each day, making it easier to feel sleepy at a predictable hour the following night. In contrast, sleeping in on weekends delays adenosine accumulation, which can make it harder to fall asleep the next evening and create a cycle of weekend drift that undermines weekly consistency.

Studies from the Sleep Research Society show that individuals who maintain regular wake times report better sleep quality, faster sleep onset, and improved daytime alertness—even when they occasionally go to bed late. This consistency helps train the body’s internal clock, making sleep more efficient over time. The goal is not perfection but reliability. By prioritizing a fixed wake-up time, individuals create a foundation upon which other healthy sleep habits can build.

Building a Pre-Bed Ritual That Actually Works

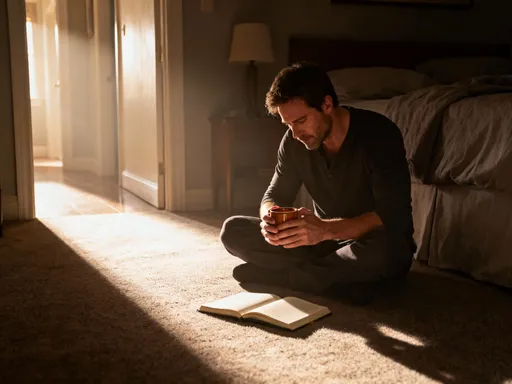

A well-designed wind-down routine signals to the nervous system that it is safe to transition from wakefulness to rest. Unlike passive activities like scrolling through social media, a purposeful pre-sleep ritual reduces cognitive stimulation and lowers physiological arousal. The key is consistency and repetition: over time, the brain begins to associate specific behaviors with sleep, making it easier to relax.

An effective routine begins 60 to 90 minutes before bedtime. This includes dimming household lights to mimic sunset, which supports natural melatonin production. Turning off electronic devices or using blue light filters helps minimize disruptive signals to the brain. Instead of screen time, engaging in low-stimulation activities such as reading a physical book, journaling, or gentle stretching can ease the mind.

Mindfulness practices, including deep breathing or progressive muscle relaxation, have been shown in clinical studies to reduce sympathetic nervous system activity—the “fight-or-flight” response that can interfere with sleep. These techniques do not require special training; even five minutes of focused breathing can lower heart rate and quiet mental chatter. Importantly, the ritual should be personalized and sustainable. It is not about adding more tasks to an already full day, but about creating a peaceful bridge between daily responsibilities and rest.

Food, Movement, and Their Role in Sleep Regulation

Diet and physical activity are often overlooked contributors to sleep quality. The timing of meals, in particular, plays a significant role in circadian alignment. Eating late at night—especially large or high-carbohydrate meals—can delay gastric emptying and increase core body temperature, both of which interfere with the onset of deep sleep. The digestive system slows in the evening, and food consumed too close to bedtime may lead to discomfort or fragmented sleep.

On the other hand, eating meals at consistent times each day helps stabilize metabolic rhythms, which in turn supports a stable sleep-wake cycle. Research published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition indicates that individuals who eat breakfast shortly after waking and finish dinner at least three hours before bed tend to have better sleep efficiency and fewer nighttime awakenings. This doesn’t mean strict dietary rules, but rather alignment with natural bodily processes.

Physical activity also strengthens circadian rhythms. Daytime exercise, particularly in the morning or afternoon, has been shown to improve sleep quality by increasing the amplitude of the body’s internal clock. It enhances the contrast between wakefulness and rest, making both states more robust. Even moderate activities like walking, gardening, or light strength training contribute to better sleep over time. The key is regularity—consistent movement throughout the week is more beneficial than intense but sporadic workouts.

Troubleshooting Common Setbacks

Even with strong habits, life sometimes disrupts sleep. Stress, travel across time zones, illness, or family obligations can throw off routines. The important thing is not to aim for perfection, but to respond with flexibility and self-compassion. When sleep is interrupted, the focus should be on gentle realignment rather than strict correction.

For example, after a late night, it can be tempting to sleep in the next morning. However, doing so can delay the entire sleep cycle and make it harder to fall asleep the following night. A better strategy is to maintain the usual wake-up time and rely on natural light and physical activity to stay alert. A short nap, if needed, should be limited to 20–30 minutes and taken before 3 p.m. to avoid interfering with nighttime sleep.

When traveling, gradual phase shifting in the days before departure can ease the transition. Adjusting bedtime and wake time by 15–30 minutes per day toward the destination’s time zone helps the body adapt more smoothly. Upon arrival, exposure to morning light at the new location quickly resets the internal clock. Similarly, during periods of high stress, returning to core habits—consistent wake time, light exposure, and a calming evening routine—can restore balance more effectively than drastic changes.

Sleep is not a performance metric, but a biological necessity. Progress may be slow, and setbacks are normal. What matters most is long-term consistency. Over time, small, science-supported choices compound into lasting improvements in energy, focus, and emotional well-being. By working with the body’s natural rhythms rather than against them, it becomes possible to sleep smarter—not harder—and reclaim the rest that supports a full, vibrant life.