Passing It On Without Paying More: My Deep Dive Into Smarter Wealth Transfer

We all want to leave something behind for the ones we care about—but why let hidden costs eat away at what we’ve built? I’ve spent years navigating the quiet complexity of passing down assets, only to realize how much can be lost without smart planning. It’s not just about wills or trusts; it’s about strategy, timing, and avoiding the traps that drain value. Too often, families assume that love and good intentions are enough to protect a legacy. But in reality, without careful financial foresight, even the most thoughtful plans can unravel under the weight of taxes, legal delays, and misaligned structures. This is what I learned when I dug deeper than most ever do—how to pass on wealth not just with emotion, but with precision.

The Hidden Cost of Good Intentions

Many believe that drafting a will is the final step in securing their family’s future. While it is an essential document, it is far from a complete solution. In fact, relying solely on a will can lead to significant financial erosion before any assets reach their intended recipients. The process of probate, which validates a will through the court system, often results in extended delays and high legal fees. These costs are paid directly from the estate, reducing the amount available to heirs. In some cases, estates spend months—or even years—tied up in legal proceedings, during which time market fluctuations or mismanagement can further diminish value.

Beyond probate, estate taxes represent another major source of wealth leakage. Though not every estate is subject to federal taxation, those that are may face substantial rates that apply to the total value of assets at the time of death. This includes real estate, investment accounts, retirement funds, and even personal property. Without planning, heirs might be forced to liquidate key assets—like a family home or business—just to cover tax obligations. This outcome contradicts the very purpose of leaving a legacy: to preserve stability, not create financial strain.

Another overlooked issue is the structure of beneficiary designations. Many people assume their will controls all asset distribution, but certain accounts—such as retirement plans and life insurance policies—pass directly to named beneficiaries regardless of what the will says. If these designations are outdated or inconsistent with the overall plan, it can lead to unintended consequences. For example, naming an ex-spouse as a beneficiary on a 401(k) could mean the funds go to the wrong person, even if the will states otherwise. Similarly, leaving a large IRA to a young adult without safeguards may result in poor financial decisions or rapid depletion of funds.

The emotional weight of inheritance decisions often overrides financial logic. Parents may feel compelled to treat all children equally, even when their financial needs or responsibilities differ. While fairness is important, true equity sometimes means unequal distributions based on circumstances—such as providing more support to a child with a disability or less to one who is already financially independent. Avoiding these conversations out of discomfort can lead to confusion, resentment, and costly litigation among siblings. The takeaway is clear: good intentions must be paired with sound financial strategy. Without it, even the most carefully written will may fail to protect what matters most.

Why Asset Location Matters More Than You Think

When planning for wealth transfer, most people focus on who will inherit their assets—but few consider how the location of those assets impacts the outcome. Not all accounts are created equal in the eyes of tax law, and transferring them improperly can trigger unnecessary liabilities for heirs. Understanding the difference between taxable, tax-deferred, and tax-free accounts is crucial to minimizing the financial burden on the next generation.

Taxable accounts, such as brokerage accounts, offer the most flexibility. When passed on, these assets typically receive a step-up in cost basis, meaning the heir’s tax liability is calculated from the market value at the time of death, not the original purchase price. This can eliminate capital gains taxes on appreciated assets, making them highly efficient to transfer. For example, if a parent bought stock for $10,000 and it’s worth $100,000 at the time of death, the heir starts with a cost basis of $100,000. If they sell it immediately, no capital gains tax is due. This built-in tax advantage makes taxable accounts ideal candidates for inheritance.

In contrast, tax-deferred accounts like traditional IRAs and 401(k)s pose a different challenge. These accounts grow without annual taxation, but withdrawals are taxed as ordinary income. When inherited, non-spouse beneficiaries must now follow the rules of the SECURE Act, which generally requires them to withdraw all funds within ten years. This compressed timeline can push heirs into higher tax brackets, especially if they are already earning income. For instance, a child inheriting a $500,000 IRA may be forced to take large distributions over a decade, each subject to income tax. This creates a significant drag on net value and can erode the intended benefit of the inheritance.

Tax-free accounts, such as Roth IRAs, offer a more favorable path. Since contributions are made with after-tax dollars, qualified withdrawals—including by beneficiaries—are tax-free. This makes Roth accounts exceptionally valuable for wealth transfer, particularly when passed to younger heirs who can stretch tax-free growth over decades. Converting traditional IRA funds to a Roth during life—while paying the taxes upfront—can be a strategic move for those in a lower tax bracket than their heirs. Though it requires paying taxes now, it shields future generations from tax liabilities later.

Real estate and business interests add further complexity. Inherited property also receives a step-up in basis, which can minimize capital gains if sold. However, ongoing maintenance, property taxes, and potential disputes among co-owners can complicate ownership. Business interests may require active management, and without a succession plan, the enterprise could falter. Transferring ownership gradually during life—through gifting shares or establishing a buy-sell agreement—can ensure continuity and reduce tax exposure. The key insight is that asset location isn’t just about investment performance; it’s about tax efficiency, access, and long-term sustainability for the recipient.

Trusts: Not Just for the Ultra-Rich

There’s a common misconception that trusts are only for millionaires or celebrities. In reality, they can be powerful tools for middle-income families seeking greater control over how and when their assets are distributed. A trust is a legal arrangement in which a trustee manages assets on behalf of beneficiaries according to specified terms. Unlike a will, which becomes public record through probate, a trust allows for private, streamlined transfer of wealth—often without court involvement.

Revocable living trusts are among the most accessible options. As the name suggests, they can be changed or revoked during the grantor’s lifetime. Their primary benefit lies in avoiding probate. By transferring ownership of key assets—such as a home, bank accounts, or investment portfolios—into the trust, those assets bypass the court process upon death. This can save time, reduce legal costs, and maintain privacy. For families concerned about public exposure of their financial affairs, this discretion is invaluable. Additionally, a revocable trust can include provisions for incapacity, allowing a designated successor trustee to manage finances if the grantor becomes unable to do so.

Irrevocable trusts, while less flexible, offer stronger protection and tax advantages. Once established, the terms cannot be altered without beneficiary consent, and the assets are no longer considered part of the grantor’s taxable estate. This can reduce exposure to estate taxes and shield assets from creditors. For example, a parent concerned about a beneficiary’s financial habits or potential divorce could set up an irrevocable trust with conditions—such as distributions for education, healthcare, or housing—rather than giving a lump sum. This ensures the funds support long-term well-being rather than being spent quickly or claimed by third parties.

However, trusts are not a one-size-fits-all solution. They require careful drafting, ongoing management, and funding—meaning assets must be formally transferred into the trust’s name. If this step is overlooked, the trust may be ineffective. There are also administrative costs, including trustee fees and potential tax filings. For smaller estates with straightforward goals, a well-structured will with proper beneficiary designations may suffice. The decision to use a trust should be based on individual circumstances: the size of the estate, family dynamics, asset types, and long-term objectives. Consulting a qualified estate planning attorney is essential to determine whether a trust adds value or introduces unnecessary complexity.

Gifting While Living: A Smarter Way to Reduce Burden?

One of the most effective strategies for reducing the size of a taxable estate is to give assets during life. This approach, known as lifetime gifting, allows individuals to transfer wealth gradually while retaining control and witnessing its impact. Rather than waiting until death, when heirs may face tax burdens or administrative hurdles, living gifts can provide immediate support—helping with education, home purchases, or starting a business. At the same time, removing assets from the estate lowers its overall value, potentially reducing or eliminating future estate tax liability.

The tax code allows for annual exclusion gifts, meaning individuals can give a certain amount per recipient each year without triggering gift tax or using part of their lifetime exemption. While specific figures change over time, the principle remains: consistent, structured gifting can move substantial wealth over time without tax consequences. For example, a grandparent giving the maximum allowable amount to each grandchild annually could transfer hundreds of thousands of dollars over a decade, all outside the taxable estate. Married couples can often double this amount by combining their individual exclusions.

Beyond the annual limit, larger gifts can be made using the lifetime gift and estate tax exemption. This unified credit covers both lifetime gifts above the annual exclusion and transfers at death. While using this exemption reduces the amount available for future bequests, it can still be a strategic choice—especially when asset values are low or when the giver expects their estate to exceed exemption thresholds. Transferring appreciating assets, such as stock or real estate, while values are modest can lock in lower tax bases and allow heirs to benefit from future growth outside the estate.

Still, gifting during life requires thoughtful consideration. Once an asset is given, it is no longer under the donor’s control. If financial needs change—due to medical expenses or market downturns—recovering the gift may not be possible. There’s also the emotional dimension: some parents worry that early gifting might reduce motivation or create dependency. Others fear perceptions of favoritism if gifts are unequal. Open communication with family members can help align expectations and reinforce that gifting is part of a broader plan, not a reflection of personal preference. When done with clarity and purpose, lifetime gifting becomes not just a tax strategy, but a meaningful way to strengthen family well-being in the present.

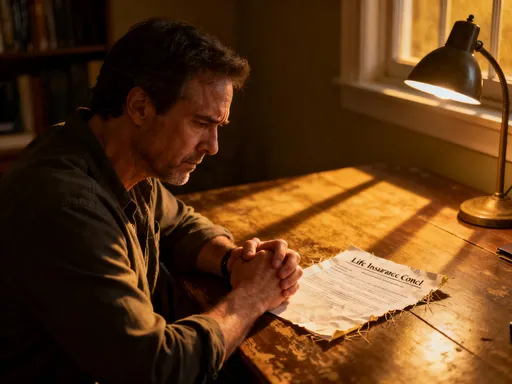

Life Insurance: The Silent Wealth Multiplier

Life insurance is often viewed solely as income replacement for young families, but its role in wealth transfer is equally significant. When structured properly, a policy can serve as a tax-efficient source of liquidity to cover estate taxes, equalize inheritances, or provide immediate financial security. Unlike many other assets, the death benefit is generally received income-tax-free by beneficiaries, making it a powerful tool for preserving net value.

For estates subject to taxation, liquidity is often a critical issue. Heirs may not have the cash on hand to pay estate taxes, forcing them to sell assets at inopportune times. A life insurance policy held outside the estate—such as one owned by an irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT)—can provide the necessary funds without increasing the taxable estate. The proceeds go directly to the trust, which then uses them to pay obligations or distribute to beneficiaries. This ensures that key assets, like a family business or real estate, remain intact and in the family.

Another strategic use is in achieving fairness among heirs. In families where one child takes over the family business, the others may receive non-business assets. To balance the inheritance, life insurance can provide equivalent value to the non-involved siblings. For example, if a son runs the farm and inherits it, his sisters could receive the death benefit from a policy, ensuring equitable distribution without disrupting operations. This approach maintains harmony and recognizes contributions without financial disparity.

Not all policies are suited for this purpose. Term life insurance, which provides coverage for a set period, is typically too short-lived for long-term estate planning. Permanent life insurance—such as whole or universal life—offers lifelong coverage and builds cash value over time. While more expensive, it can be integrated into a broader financial strategy. However, it must be managed carefully. Overfunding a policy or misunderstanding its terms can lead to inefficiencies. As with any financial tool, life insurance should be evaluated in context, not as a standalone solution. When aligned with estate goals, it becomes a silent multiplier—delivering value precisely when it’s needed most.

Family Dynamics and Financial Realities

No wealth transfer plan succeeds without considering the human element. Even the most technically sound strategy can fail if it ignores family relationships, communication gaps, or differing expectations. Money has emotional weight, and unspoken assumptions about fairness, responsibility, or obligation can lead to conflict after a loved one’s passing. Addressing these issues in advance is not just wise—it’s essential for preserving both financial and emotional legacies.

One of the most common sources of tension is the assumption of equal treatment. While many parents strive to divide assets equally, true fairness sometimes requires differentiation. A child with special needs may require ongoing financial support, while another who achieved financial independence may not. Providing more to one heir is not inherently unfair—it reflects responsibility, not favoritism. The key is transparency. Discussing the reasoning behind decisions while the grantor is alive allows heirs to understand the intent, reducing the risk of misunderstanding or resentment.

Conversations about money are often avoided due to discomfort or fear of appearing greedy. Yet delaying these discussions can leave heirs unprepared and vulnerable to poor decisions. Educating children about the family’s financial values, the structure of the estate plan, and the responsibilities that come with inheritance fosters financial maturity. It also helps prevent dependency—ensuring that wealth supports, rather than replaces, personal initiative. Sharing stories of how wealth was built—through hard work, sacrifice, and discipline—can instill respect and stewardship.

In blended families, the challenges are even greater. Remarriage introduces stepchildren, new spouses, and competing loyalties. Without clear planning, assets may not go where intended. A surviving spouse might inherit everything, leaving biological children with nothing if the spouse remarries or changes their will. Using trusts or designated beneficiary accounts can protect both the spouse and children, ensuring that each receives their intended share. Again, open dialogue reduces ambiguity and builds trust across generations.

Ultimately, the goal is not to eliminate emotion from inheritance, but to integrate it with financial logic. A plan that respects both practical needs and personal values is more likely to endure. By addressing family dynamics proactively, individuals can pass on not just assets, but wisdom, unity, and peace of mind.

Building a Plan That Lasts Beyond You

Creating a lasting wealth transfer strategy is not a one-time event—it’s an ongoing process of assessment, alignment, and adjustment. The first step is conducting a comprehensive audit of all assets: financial accounts, real estate, business interests, insurance policies, and personal property. Each should be evaluated not only for value, but for how it will transfer and what tax or administrative costs may apply. This inventory reveals potential leakage points—accounts with outdated beneficiaries, assets stuck in probate, or inefficient ownership structures.

Next, goals must be clarified. Is the priority to minimize taxes? To protect a vulnerable beneficiary? To keep a family business running? To treat children fairly while recognizing different needs? Answering these questions shapes the choice of tools: wills, trusts, gifting strategies, insurance, or a combination. No single solution fits every family. What matters is alignment—ensuring that the plan reflects both financial objectives and personal values.

Professional guidance is invaluable, but it should be collaborative, not directive. Working with a team that includes an estate planning attorney, a tax advisor, and a financial planner ensures comprehensive coverage. However, no advisor should operate in isolation. Regular coordination among professionals prevents conflicting advice and ensures consistency. More importantly, the individual remains in control—making informed decisions based on expert input, not delegation.

Finally, the plan must be reviewed regularly. Life changes—marriage, divorce, births, deaths, career shifts, market movements—all affect estate dynamics. A plan drafted decades ago may no longer reflect current realities. Annual check-ins, especially after major life events, keep the strategy relevant and effective. Digital tools and estate planning software can help track documents, deadlines, and beneficiary updates, adding another layer of organization.

In the end, passing on wealth is about more than money. It’s about legacy, care, and responsibility. By planning with intention, families can ensure that what they’ve built endures—not diminished by avoidable costs, but strengthened by wisdom, foresight, and love. The greatest inheritance is not just what is given, but how it is given.